As a Brit who has grown up through the 1980s, I can say with some conviction that the notion of a very British, stiff upper lip dystopia with all of the nightmarish trimmings that might go along with that is one that both appalls and compels me. We Happy Few encapsulates this ordeal almost perfectly; fashioning a dystopian hellscape that is rich in satire and social commentary, but which sadly doesn’t boast a good enough game to compliment it and do its astounding setting proper justice.

We Happy Few’s Dystopia Is A Compelling Nightmare Unlike Any Other

A first-person adventure that packs in a range of action, RPG and stealth elements into its creative fold, We Happy Few whisks players off to the fictional British 1960s town of Wellington Wells, where the population are under the thrall of a psychotropic drug called ‘Joy’. Much more than just an ‘upper’ to perk yourself up with, Joy makes everyone manically cheerful with the creepy effect being magnified by the silver face masks that the various denizens of Wellington Wells adorn themselves with.

And of course, this wouldn’t be a dystopia if there wasn’t a conformity dynamic involved where you must blend in with the rest of the hopelessly indoctrinated souls if you want to survive. Speaking of which, it is actually the very notion of conformity that not only stands as a cornerstone of We Happy Few’s dystopian setting, but also one that bleeds through into the game itself.

As one of three individuals who have decided to shun the regime and escape the clutches of Wellington Wells, you must dress and act like your Joy-addled compatriots lest they catch wind of your insubordination and beat a hole in your face with a cricket bat/rolling pin. The kicker however, is that away from the hustle of the central town, there are various hamlets and villages stuffed with vagrants and mentally broken folk. Pointedly, these are people who have rejected Joy and are attempting to piece their lives together, and if you want to blend in with them, so too must you look like them and mirror their affinity for torn clothing in order to fit in.

It’s a superb setting that’s brimming with lore, stories and a real sense of unease quite unlike any other. Awash with vibrancy and color, it’s fair to say that We Happy Few’s dystopia is quite the visual treat too, as lush forests and woodlands give way to brightly hued streets, towns and estates. After all, in a town where everyone is supposed to be murderously happy 24/7, having dull and miserable color schemes just won’t do now will it?

As such, We Happy Few’s cheerfully terrifying environs are a world away from what we’re used to, and the game is all the more refreshing for it.

We Happy Few Is A Jack Of All Trades But Master Of None

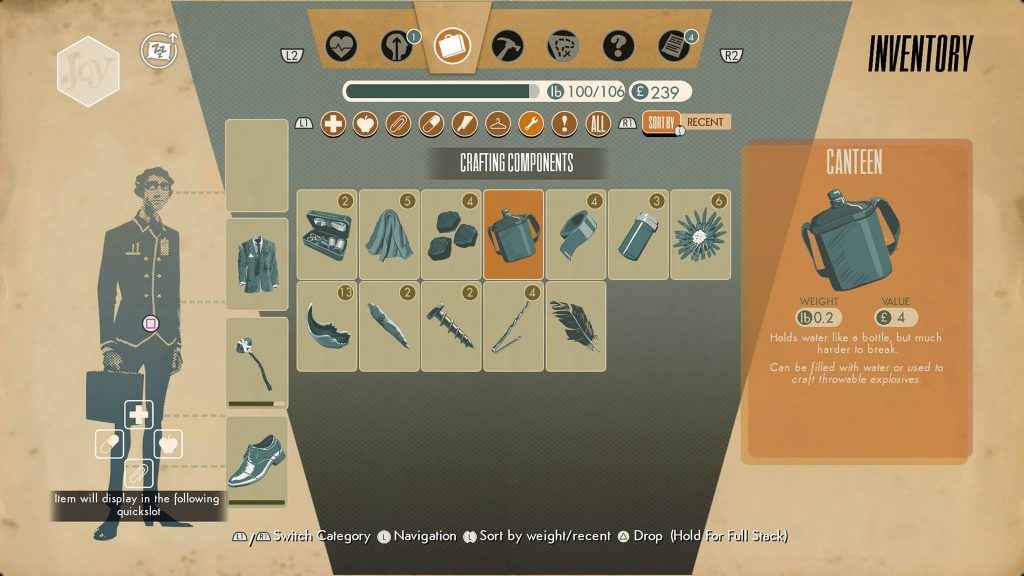

We Happy Few has you doing a bit of everything. Once you’ve gotten through the first 10-15 minutes of opening story exposition and linear exploration, you’ll be thrust out into the big wide world where you are free to roam about the place, taking quests, progressing the story, crafting new gear and of course, increasing the capabilities of your character.

The problem is, though We Happy Few lets you do a bit of everything, it doesn’t do any one particular thing all that well. Take the AI side of things for example – in We Happy Few if you act strangely or go into someone’s house without their permission you can rightly expect a shower of violence to be headed your way from the local NPCs, the problem is, once they give chase and you outrun them, they completely forget anything that happened beforehand which in turn, allows you to just stealth steal everything from people’s houses if you’re patient enough.

Speaking of stealth, We Happy Few is somewhat spotty in it’s execution. Compulsion Games latest apes the status quo in having detection indicators above the heads of your foes so you can tell if you’ve been spotted or not, and continues to replicate what you’ve already seen elsewhere with bottles and rocks being used to distract enemies and so on. Equally, enemies can sometimes stare at you for three to four seconds before they identify you as a threat. To say it’s nothing revelatory, or indeed a touch broken, would be quite the understatement.

The combat too is largely perfunctory. Largely played out with melee weapons, you can block, attack and, well, that’s pretty much it. There are no special counters, no parrying abilities to speak of – just block and attack, meaning that the combat gets boring rather quickly indeed so long as you pick your strikes and conserve your stamina sensibly.

Away from such violent pursuits, conversation with the numerous denizens of Wellington Wells is also largely unremarkable. When you’re not speaking to pre-scripted story folks, all you’ll get is your character saying some random phrases like “How did we get like this?” and the response that comes back is largely irrelevant and nothing to do with what you’ve asked. Again, it’s hardly encouraging and when a game such as We Happy Few invests so much in its admittedly engrossing setting, you expect to have such an interesting world filled with equally interesting people to interact with – something that is certainly not the case here.

Still, it’s not all quite so ho-hum. The side quests are a highlight, because not only does completing them reward you with experience points that can be put into a number of skill trees, but so too they delight with their oddity. From dealing with a family of weirdos trying to cook some soup using an apparently demonic rubber duck, to eating magic mushrooms at night and Arthur trying to make a remedy to make him vomit, it’s clear these aren’t your usual side quests and they are all the better for it.

We Happy Few Needed Longer In Development

Where We Happy Few stumbles further is in aspects of its technical design – simply put, the game needed at least another six to nine months of development to iron out a litany of rough edges and provide some much needed polish. Visually We Happy Few is remarkable simply on account of its admittedly astounding retro futuristic aesthetic, but technically it’s inconsistent with a range of blurry low detail textures, a variable sub 30 FPS frame rate, very long initial loading times and plenty of texture pop in. This is hardly PS4 Pro or PS4 showcase material.

Further hurting the audiovisual presentation of We Happy Few are the numerous bugs and glitches that are scattered throughout the game. From character models that get stuck in and float up walls, to items that just fall through the floor (not fun when you need those items), it’s clear that the game needed a little longer in the oven than it ended up with. There are even some areas of the map that clearly haven’t been finished too – with flat textures and no additional detail or objects to speak of; again, proof that We Happy Few needed more development time than it actually got.

Then there are some basic quality of life things that We Happy Few doesn’t get quite right. When you reload a saved game it simply puts you back at the last fast travel hub you encountered, the in-game map doesn’t update when you complete dig sites and quests, and bodies that lay in the darkness aren’t highlighted in the UI for easy discovery. Once more these are all niggles that could have been ironed out with additional development, and will now have to be addressed by extensive patching in the forthcoming weeks and months.

That said, We Happy Few’s presentation does have one highlight that exists beyond its enticing aesthetic – the voice acting performances. Perfectly capturing the pulpy Britishness of the 60s and beyond, everybody in We Happy Few (especially Arthur and his amusingly dry monologues), sounds resolutely believable in the roles both as thralls of the system and also as just a series of broken people trying to break out of Wellington Wells and atone for past sins.

We Happy Few Is A Flawed Though Entertaining Dystopian Romp

By the time the end credits roll on We Happy Few, it’s difficult to shake the feeling that its social satire and refreshing dystopian vision ends up being more enjoyable than the game that sits beneath it. In part this is owed to the fact that We Happy Few came out of development far too quickly – a fact that the range of rough edges and unpolished elements readily attest to.

The other issue is that many of the systems that We Happy Few employs are executed in a distinctly roughshod fashion. Indeed, after that initial of hit sweet euphoria, where We Happy Few nearly convinces you that it is some sort of beautiful lovechild of Bioshock and The Elder Scrolls, extended play proves that such comparisons are ill-founded as the game starts to come apart at the seams and appears far less compelling than its brilliant setting would otherwise indicate. All the same, We Happy Few is still very capable of providing fun and entertainment, just be sure to be in a forgiving mood for its more egregious range of flaws.

We Happy Few is out now on PS4, PC and Xbox One.

Review code supplied by publisher.